Houston’s Flood Tunnel Debate: Size and Strategy Matter

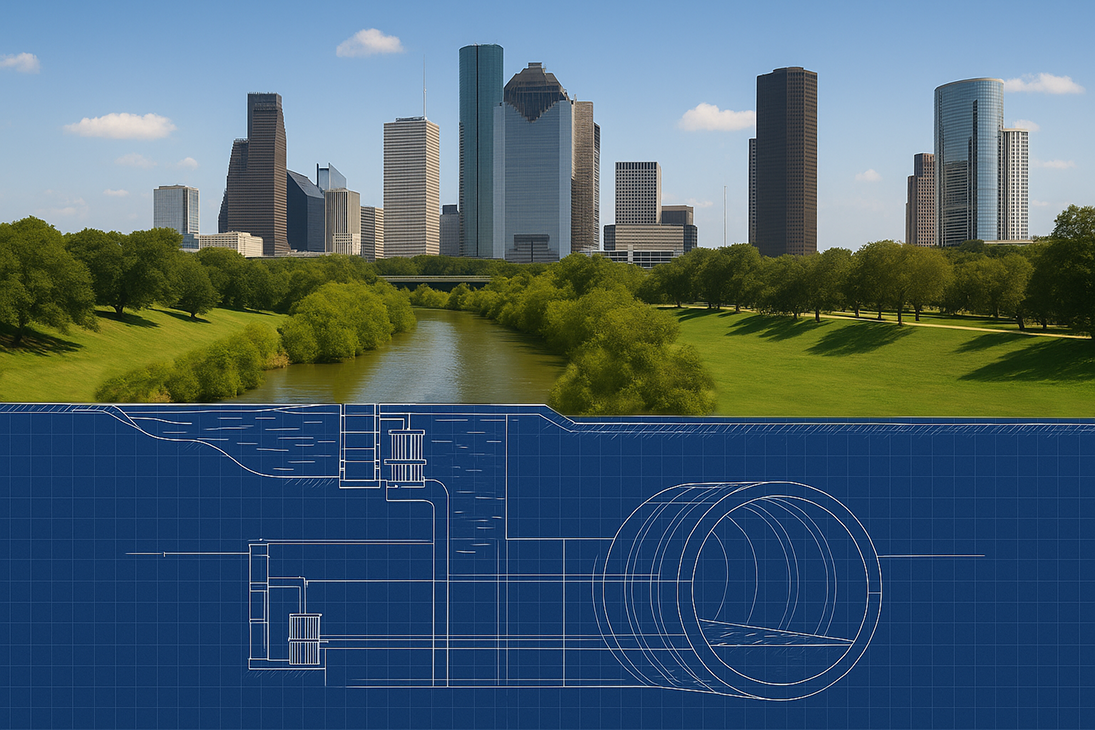

As a Canadian-turned-Texan with nearly five decades in Houston, I’ve seen our city battle floods with grit and ingenuity. The esteemed Houston Chronicle recently questioned the undeniably brilliant Elon Musk’s claim that his Boring Company’s 12-foot-diameter tunnels, used in Nashville, could solve Houston’s flooding for a fraction of the Harris County Flood Control District’s (HCFCD) $4.6 billion, 36-foot-diameter tunnel plan. After crunching the numbers, I find Mr. Musk’s idea innovative but inadequate for Addicks Reservoir - though the tunnel’s untapped potential could fight both floods and subsidence.

HCFCD’s 26 mile long, 36-foot tunnel is engineered to divert 4,000 to 12,000 cubic feet per second (cfs) from Addicks Reservoir to the Houston Ship Channel, preventing repeats of Hurricane Harvey’s 2017 dam-release flooding. A 36-foot tunnel holds 1,018 cubic feet per foot—nine times the 113 cubic feet of a 12-foot tunnel. Manning’s equation reveals the larger tunnel conveys 19 times more water. Head loss, calculated via Hazen-Williams, underscores the gap: at 4,000 cfs, a 12-foot tunnel loses 5,483 feet of elevation over 26 miles, versus 26 feet for the 36-foot tunnel—a 210-fold difference. At 12,000 cfs, the smaller tunnel’s losses reach 41,945 feet, rendering it impractical.

Scalability matters both to Silicon Valley and to the Houston Planning Commission, and this is where Musk’s “add more tunnels” pitch falters. Matching one 36-foot tunnel requires 19 parallel 12-foot tunnels, escalating excavation, land, and maintenance costs, as engineer Larry Dunbar and Commissioner Tom Ramsey note. Nashville’s 12- foot tunnels, handling 1,000-2,000 cfs at $50-60 million per mile may suit urban drainage but not Addicks’ 12,000-cfs mandate, set by 1930s Corps designs and proven critical during Harvey’s emergency releases to protect the dam and upstream homes.Why is Addicks important to this equation? Lawsuits from Buffalo Bayou property owners have constrained outflows, risking dam failure. A 12,000-cfs bypass in 2017 could have saved thousands of downstream properties. Musk’s citywide tunnel idea misses this reservoir-specific crisis and The Houston Chronicle’s skepticism is justified: cheaper isn’t better here.

Yet, HCFCD’s tunnel offers more than flood relief. Its 3,300 acre-feet of storage, or 1.07 billion gallons, equals two days of Houston’s water production or detention for 7 square miles of runoff. Refilled 3-5 times yearly with pumps and filtration, it could offset 300-500 million gallons of irrigation water, saving $50-100 million annually at $0.005 per gallon. As I’ve noted on subsidence (42% of Houston sinks over 5 mm/year), reducing groundwater use via stormwater reuse could slow our sinking, easing pressure on aquifers like the Chicot and Jasper, mirroring the Harris-Galveston Subsidence District’s success.

HCFCD’s large tunnel is essential for Addicks, but Musk’s modular approach could aid smaller bayous. To avoid crafting a budgetary chimera, a monstrous blend of mismatched solutions, we must balance cost and scale. A hybrid model, pairing a core tunnel with smaller feeders and reuse, could maximize value. How will Houston transform floodwater into a resource? That’s our next challenge.

Dr. Culp is the most senior hydrologist at Tetra Land Services and has three decades of civil engineering experience. His Ph.D. scholarship studied the effectiveness of structural BMP for the control of storm water pollution in Harris County while performing water quality monitoring and modeling upon selected ponds for the county. Dr. Culp also co-authored the City of Houston stormwater quality management plan. He is one of Texas’s original Certified Floodplain Managers. Recently, Dr. Culp and his staff have developed a series of drainage studies for Industrial and Oil Majors along the Texas Gulf Coast. Culp is married with two children, and lives on his farm in Southwest Houston.